So far, most of the greatest venture “N-of-1 outcomes” have had their origins in Silicon Valley. That dynamic is changing. When LPs, entrepreneurs, and investors ask us if N-of-1 companies can rise from other ecosystems, we say yes and point to one of our own Indian portfolio companies, Shiprocket.

Shiprocket is enabling large swaths of e-commerce transactions in India by embracing the idiosyncrasies of their market – versus forcing them to conform to known models. Shiprocket is aggregating an atomic unit of value, or a “raw resource” that catalyzes innovation: the Indian E-commerce Transaction.

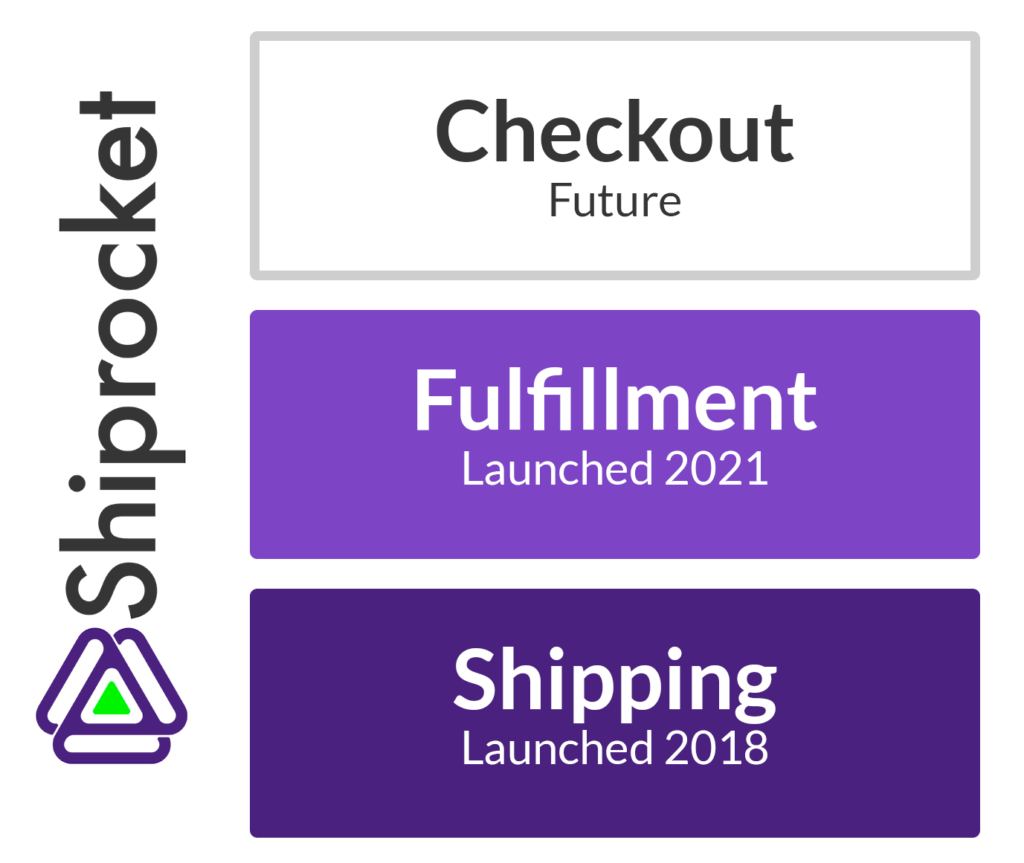

Logistics and payments infrastructure in India are nascent and fragmented, and social media, which has been one of the main drivers of internet adoption in India, has emerged as a place of business. Through experimentation and deep familiarity with Indian e-commerce, Shiprocket identified how to capture this unit of value, and is on the path to dominating it by vertically integrating all elements necessary to unlock it: shipping, fulfillment and checkout. The result: Shiprocket will emerge as the infrastructure that allows themselves and companies on their platform to build new products leveraging the transaction as a dependency.

At Tribe Capital, we believe that early-stage product-market fit is observable – it is not an abstract concept but rather something that can be measured, identified and amplified. When it manifests, product-market fit persists through successive orders of magnitude. In its most extreme, product-market fit is exemplified in what we refer to as an N-of-1 outcome, where a company is so successful that an entire market is created based on the utility of the company’s core product.

In emerging markets, and India especially, where the market has largely not yet built its core economic infrastructure, we have discovered that even more such opportunities exist. To this end, Shiprocket is building the missing infrastructure for Indian E-commerce transactions by embracing the structural idiosyncrasies of the Indian e-commerce value chain.

In this note, we discuss how Shiprocket has…

- Recognized that failing logistics and payments infrastructure are leading to a dislocation in Indian e-commerce and unmet demand is restricting growth and built a mechanism to aggregate Indian e-commerce transactions by solving the shipping and logistics problems in ways unique to the Indian market

… and has a path to …

- Vertically integrate fulfillment and checkout while passing on the benefits from higher reliability and lower prices to their core merchant customers

… with an ultimate N-of-1 outcome when …

- Shiprocket translates its unique capture of e-commerce transactions, coupled with access to capital and the means to distribute it, to provide capital solutions including both working capital and enablement to merchants, and point-of-sale financing for consumers

Shiprocket’s origins: deep market knowledge and experimentation

In 2012, Saahil Goel and Gautam Kapoor (later joined by co-founders Vishesh Khurana and Akshay Ghulatis) created Kartrocket to build e-commerce storefronts and checkout experiences. They drew inspiration from Shopify and its related success in the US, allowing merchants to build customized web stores. The initial premise was that India needed a platform that could support direct sellers outside of Amazon, and that they had identified the missing infrastructure needed to catalyze widespread growth.

As they began operating, it was apparent that trust between merchants and consumers in Indian e-commerce was low, and crucially, payments and delivery reliability was abysmal. Kartrocket adoption was mixed, and in the intervening years as Saahil and Gautam continued experimenting, a few idiosyncrasies emerged in India.

- Proliferation of cheap smartphones and practically free mobile data

- Whatsapp and Facebook Groups emerged as places for small merchants to sell goods

Then there was a clue: medium and large merchants would buy Kartrocket just for the purposes of integrating with Magento or Shopify which offered ~$10 shipping. Why buy storefront and checkout integrations just for the shipping?

This led them to the realization that the Indian E-commerce Transaction (the confluence of successfully checking out, completing fulfillment, and shipping the package) was failing – not the storefront. “Return to Origin” rates, when a delivery fails such as if the consumer rejects it or because the destination was not found, were, and still are, a staggering 20-25%.

They gave a team of 5 engineers and 1 product manager 6 months to explore, and they quickly saw the opportunity was immense. They launched Shiprocket in 2017, and in early 2018 they made the core web shop free, and monetized transactions instead.

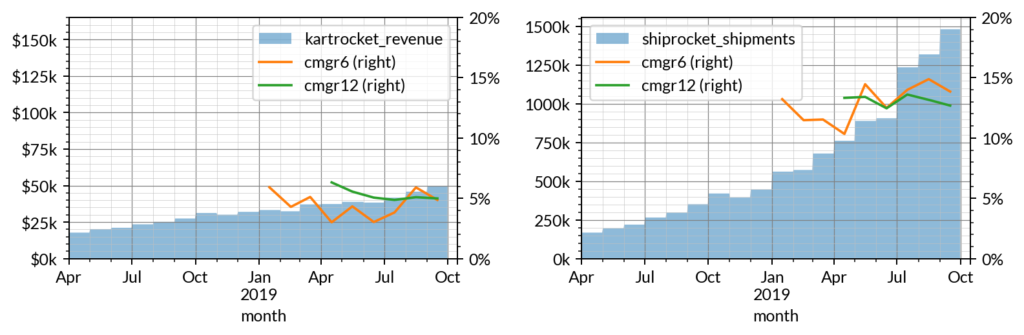

Shiprocket’s goal is to make shipping and logistics for merchants so simple that it could be available to every merchant, no matter their size or sophistication. Over the 18 months from April 2018 to October 2019, the new Shiprocket product rapidly dominated their business. Their business model: charge the merchant more than the courier charges Shiprocket when a package is shipped. Why could they exert this pricing power? Because without their vertically integrated approach, the transactions they were facilitating would have never happened.

Put in context, Kartrocket grew at a decent rate of 2x year over year since inception, but during this 18-month period, the new Shiprocket courier aggregator product grew 10x in volume, processing 1.5 million shipments a month by October 2019. Today, this divergence continues to persist through successive orders of magnitude, and has reached over 10 million shipments a month.

We believe that Shiprocket’s true upside from here is not just one but possibly two orders of magnitude Why? Because they have built the core infrastructure to bring an entirely new market online: Indian E-commerce.

If you can’t pay and can’t receive a package, you can’t buy goods online

Market structure and geography matter when great opportunities emerge, and the greatest opportunities capture new, generation-defining units of value that we call atomic units.

- An atomic unit of value is a new raw resource that emerges due to changes in technology or market structure that, when captured, catalyzes an immense wave of innovation.

- Developing markets are ripe sources for new atomic units.

- We call a company N-of-1 when they completely dominate an atomic unit of value and an ecosystem emerges around their core product.

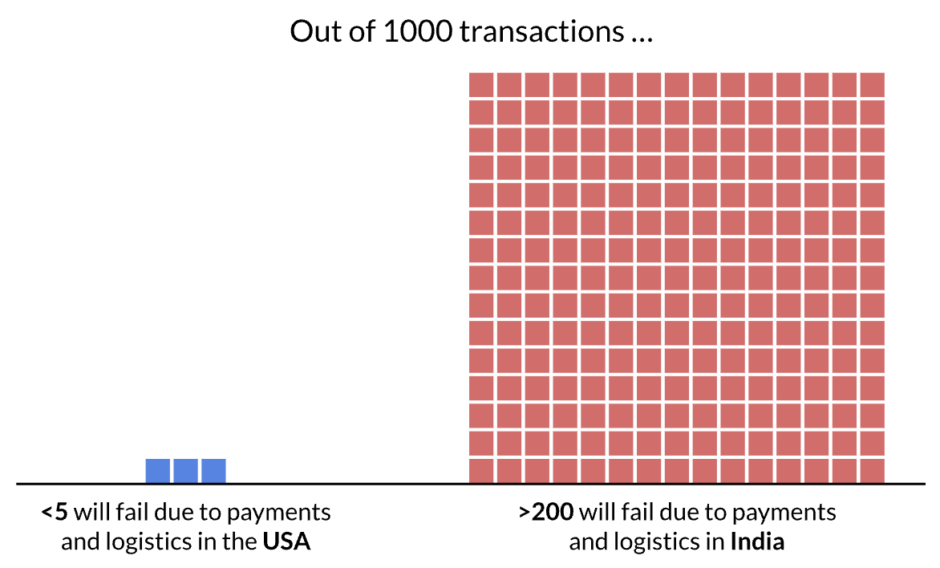

A common pitfall for international companies is trying to exactly replicate the products and playbooks of U.S. firms in their own respective markets. Notably, two key elements existed in the U.S. during the rise of e-commerce in the late 1990s and early 2000s that are notably underpenetrated or fully absent in India: 1) wide adoption of consumer credit and 2) reliable, transparent and affordable shipping and logistics.

In India, core enablers of e-commerce, logistics and payments, are presently the largest barrier to adoption. Note that when the U.S. e-commerce market formed, these services were both mature and functioning. This difference between market structures is the reason why capturing the atomic unit of the Indian E-commerce Transaction cannot be done the same way it was done in the U.S. – and the core rationale for why we think an N-of-1 opportunity exists.

At the same time, market developments in India opened up possibilities not present in North America – merchants began selling via Whatsapp and Facebook, and cheap smartphones began proliferating in India as the most common channel for internet access. This is precisely why the attempts to exactly mirror what worked in the U.S. have failed, and why we believe the N-of-1 outcomes in India will be different from what a naive observer would believe them to be by simply pattern matching to the U.S.

Below we highlight differences in infrastructure between the U.S. and India when e-commerce started taking off.

- Credit – Credit cards were largely adopted in the U.S., with over $700B of total revolving consumer credit in the late 1990s. India, in contrast, has nearly no credit for consumers and approximately 40% of larger Tier 1-2 cities (e.g. Delhi) is paid as COD (cash on delivery), with this figure reaching approximately 90% in smaller Tier 3-4 cities.

- Logistics – When e-commerce started gaining traction, logistics was nearly 100 years old in the U.S., had over 50 years of operation since the interstate highways system was constructed, and had over 30 years of adoption of electronic load boards. In contrast, India’s 3PL (third party logistics) industry is nascent, and something as simple as package tracking and package weighing are either not possible or erroneous due to poor infrastructure and, at times, manipulation. Additionally, Indian residential areas lack clearly delineated maps – a customer might list an address as “the house past the telephone pole”.

- Checkout – U.S. e-commerce was adopted in the earlier days of the internet, with main access points through people’s PCs and home internet. In India, mostly people access the internet through smartphones and via social media.

Compounding the problem, onboarding with an Indian courier is a major undertaking; good prices and services are typically reserved for very high-volume enterprise merchants. As a result, most couriers are not equipped to easily and cheaply onboard smaller merchants, and MSMEs (micro, medium and small enterprises) are significantly underserved and overpriced. Shiprocket’s insight was that transactions are not limited because products that consumers want to buy are difficult to find, but because in India, sellers lack the tools to navigate the fragmented logistics market.

Exemplifying the failings of payments and logistics infrastructure in India is the “Return to Origin” (RTO) rate. An RTO happens when there is a package delivery attempt, and due to failures in payments or logistics, the package is shipped back to the merchant, and the merchant pays twice. Over 20% of packages in India are RTO.

Since RTO’s are shipped twice, this means that over 1/3 of all shipping costs are wasted on RTO.

And this is the tip of the iceberg of the true cost, since all parties and all participants are facing constant violations of trust. Some examples where RTO happens:

- The customer has changed his/her mind and does not want the package

- The customer does not have cash to receive the package

- The order was fraudulent, and completed with false information

- The customer could not be located or contacted for the final stretch of last-mile delivery

- The delivery address is invalid

- The last-mile courier or 3PL doesn’t want to go through the trouble to complete the delivery

This problem is not specific to MSMEs but it is most pronounced for MSMEs. Over 60 million MSMEs are estimated to operate in India today. This is what we call the “fat, long tail” of e-commerce in India, and the proliferation of WhatsApp and other social networks in India as a place of commerce paints a dramatically different market structure in India than in the United States. Indian MSMEs tend to have a large personal stake in the merchandise sold. They are also new to e-commerce and have a terrible courier experience and are understandably demanding customers.

Recognizing opportunity: Taobao as a reference point for embracing idiosyncrasies instead of trying to control them

Sometimes, in new geographies for example, people see a market and believe the atomic unit will translate or is the same, instead of asking “what was the fundamental reason why that solution worked in the first place?” There is hardly a better example than Taobao’s success in China.

To understand Taobao’s N-of-1 outcome, we can draw a comparison to Ebay. Back in the early 1990’s, Ebay originally rose from the novel online auction mechanism in the early 1990’s when it created the first customer-to-customer (C2C) platform, and sites mimicking Ebay’s auction model started to form around the given Ebay’s success in the USA. After Ebay’s IPO in 1998, flush with cash it started expanding globally, mostly through acquisitions.

Ebay moved to acquire their Chinese analog and market leader EachNet, and over the course of 2002-2003, Ebay built a stake and eventually fully acquired EachNet. At this time, Ebay’s EachNet held 72% market share in C2C e-commerce.

Around this time, Alibaba, which was founded just a few years prior, launched Taobao. Compared to EachNet and Ebay together, Taobao had no customers and no resources. It might seem Taobao had no chance. However, Ebay / EachNet were designed around the Auction, but Taobao was designed around an atomic unit: the Store. In this case, the Store is where a seller posts an item for sale in a customized channel on Taobao’s ecosystem. Jack Ma is famous for saying “Ebay may be a shark in the ocean, but I am a crocodile in the Yangtze River.”

Ebay had a value proposition where a seller was able to discover the best price they could earn from selling an item. As this was the case, Ebay centered its monetization around earning a share of the transaction, often upwards of 10%. This contrasted with Taobao’s 0% fees. Even today, transaction fees are very low, under 1%. Their revenue from transaction volume is de-minimis. In its original form, Taobao also did not manage any of the payments or logistics.

In China, the proliferation of counterfeit goods, and the (at the time) underdeveloped payments and logistics infrastructure meant that building a reputation, and having to pay money to get preferential listing placement incentivized legitimate goods to be the most viewed. Because of this, Taobao emphasized the Store.

All of the traditional approaches that someone creating an e-commerce platform would try to monetize, such as transaction volumes, were initially left untouched. When we say identifying an atomic unit comes from a bottoms up approach this is exactly what we mean. It is obvious in retrospect that this worked but impossible to know in the moment, absent incredible insight available only to those who are free from assumptions about how their product should work, who sense demand signals and pour fuel on them. Merchant customers and Stores represent the majority of Taobao’s revenue in the form of advertisements.

Taobao scaled and cemented its N-of-1 outcome by vertically integrating with sister products under Alibaba (Ant Financial, named after Jack Ma’s “ant army”). Payments was a major bottleneck, for example due to the lack of widely available credit among Chinese consumers. This move was Alibaba’s way of building the infrastructure and vertically integrating the offerings around the Taobao ecosystem to serve a need that existing financial institutions and products fell short of: e-commerce payments. Ant Financial solved many of the trust and payments issues by serving as an escrow account for buyers. And because of how vibrant Taobao’s ecosystem had become, all participants were playing a repeat game, and all dependent on Taobao as a utility.

With these themes in mind, let’s return to Shiprocket.

Shiprocket is aggregating the Indian E-commerce Transaction

Shiprocket recognized that the existing Indian e-commerce infrastructure was failing. It was omitting huge swaths of the potential market, which found novel distribution through social platforms but had no merchants to facilitate delivery, compounded by a fragmented logistics landscape. Furthermore, Indian couriers were not able to build products to effectively service the “fat long-tail”.

The goal for Shiprocket is simple: let anyone in India be able to complete an e-commerce transaction – not a small undertaking by any means. The crux was devising an approach that did not require a large balance sheet and rebuilding the entire Indian logistics system from scratch. Instead, Shiprocket had the insight to bundle thousands (today, hundreds of thousands) of customers together to interface with Shiprocket, and then Shiprocket would interface with couriers.

This is the so-called courier aggregator approach: couriers, who paid billions of dollars to build their fleets over decades, and who are accustomed to onboarding large merchants but not thousands of small ones, onboard and interface just with Shiprocket, and Shiprocket manages the merchant.

This means in addition to integrating with the merchant, Shiprocket needed to integrate with the full supply chain to facilitate honoring a transaction:

- Inventory management and pricing

- Managing order fulfillment

- Courier routing and finding the cheapest, most reliable courier partner

- Label printing and invoicing

- Package tracking and lineage

- COD payments management

- RTO (return to origin) and returns

Shiprocket built software augmentations for the entire process, and charged a spread on the courier’s pricing. They earned the right of pricing power by being the core, vertically integrated infrastructure without which these transactions would never have occurred.

On top of vertically integrating this supply chain connectivity, Shiprocket is also acquiring and managing the “fat long-tail” merchants, a problem that was too challenging for the incumbent couriers to begin with, in addition to servicing their users. Recall this set of merchants is new to e-commerce and, slammed with high RTO rates and poor telemetry, and are in need of attention, products and education.

Shiprocket approached this by creating a rapid fire API factory. They built thousands of integrations, automations and rapidly iterated on their UX throughout the process of discovering what it takes to bring new merchants online.

- Shiprocket’s core customers are new merchants and new market participants. Shiprocket built a new market, rather than taking market share in an existing one.

When we talk about atomic unit capture to create a new N-of-1 utility, this is what we mean: the creation of a new market by unlocking e-commerce transactions.

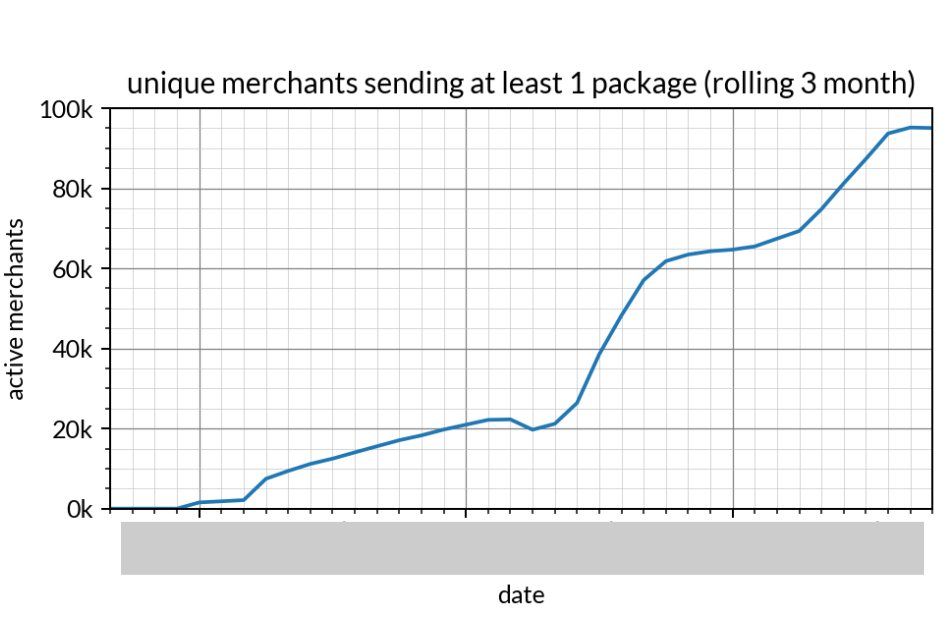

Before Shiprocket, the Indian MSME e-commerce market was notoriously a fool’s errand. But the classic characteristic of emerging N-of-1 product-market fit is that naysayers shun the market, claiming it is too small or does not exist. This is because through the organic discovery process a new market is identified and has no direct analog. In 2019, Shiprocket’s courier aggregator pivot confused investors. How could it be possible that Shiprocket makes any money or any semblance of a sustainable business from the (supposedly) least appealing customers? Fast forwarding to early 2022, nearly 100,000 unique merchants were participating on Shiprocket’s platform over the trailing quarter.

Shiprocket took a bottoms up approach to discover what was needed specifically in India, instead of translating what worked in different markets with different problems.

Shiprocket’s rapid fire API factory created a foundation for vertical integration, resulting in unbelievable margins and unit economics. It built a product suite on top of this backend infrastructure to facilitate the entire shipping and logistics process, driving retention, efficiency and pricing power. Shiprocket was not only growing, with positive gross margins, but it was profitable. India has indeed attracted more venture capital and investment today than ever before, but it still greatly lags other regions given the innovation happening in the country. Capital efficiency in India, unlike in the US startup ecosystem, is a major competitive advantage. Because of these capital considerations, Shiprocket’s profitability while bootstrapping is why it won the Indian E-commerce Transaction.

Over 24 months, Shiprocket went from being a de-minimis share of volume to over 5% of all volume for the largest Indian couriers. This positions Shiprocket as one of the couriers’ largest demand channels. Where Shiprocket was once beholden to the terms of its couriers, the power dynamic is beginning to invert where Shiprocket’s influence over a large swath of merchant demand allows them to command better terms and quality for their merchants.

Shiprocket’s unbounded upside is possible through vertical integration and becoming the gateway to unleash capital markets into its ecosystem

There is a subtle and overlooked truth that the infrastructure US e-commerce companies have leveraged does not exist in India.

If you can’t pay and can’t receive a package, you can’t buy goods online.

Shiprocket’s N-of-1 opportunity exists because existing infrastructure could not be repurposed to facilitate e-commerce transactions.

A natural question is to ask “why does this problem exist at all?” The driving reason is the nascency of the forces at play that have recently presented the Indian E-commerce Transaction as a viable source of value capture.

There is the semblance of a logistics infrastructure which has been ineffectively deployed to service the organic growth of e-commerce demand in India. The courier’s core go-to market, along with the typical purchasing patterns of Indian consumers, are in a period of change, leaving a gaping hole for an innovator to bridge the gap and unlock this market.

The rapid adoption of social media and mobile phones as a place of business exemplifies the emergence of new selling and purchasing habits. Notably this market is still de-minimis as compared to its potential, and the shift has just started. Even though the Indian e-commerce market is growing by 30% every year, the long tail is growing over twice as fast. This is what we mean by capturing a new market: the participants who are being brought online by Shiprocket are not won in a red ocean battle. They are new to the internet and not in contention between multiple providers. Shiprocket is becoming the enabling force for Indian MSMEs to transact online.

Further, Shiprocket launched and is scaling fulfillment, and will soon launch checkout to complete their vertical integration effort to facilitate transactions. As we’ve discussed at length, fragmentation and missing payments and logistics infrastructure are starved for a utility to solve this fundamental need for Indian e-commerce to exist.

In order for the infrastructure to flourish, a new utility is needed to integrate across India’s fragmented payments and logistics.

In order for a transaction to be completed, the user needs to 1) complete checkout, 2) the package needs to be fulfilled, and 3) the package needs to be delivered. In the US, this problem was solved first on the side of checkout. In India, that approach automatically fails because of the underdeveloped logistics infrastructure. Shiprocket’s approach turns this on its head.

- Solve shipping to unleash the sleeping army of MSMEs into e-commerce and build an ecosystem for merchants and couriers

- Solve fulfillment to step function SLAs, customer experience, and cost structure. Pass all of the benefits from vertically integrating fulfillment onto couriers to continue to aggregate as many transactions as possible

- Solve checkout to complete the vertical integration, tracking, shorter SLAs, and integrating new payments backends into the process. Approach this just like shipping: be an ecosystem for all of the emerging innovations in Indian payments (lending / BNPL, etc) that lack distribution to find their own product-market fit.

Shiprocket is on track to build an N-of-1 outcome due to a number of factors: a wedge (shipping and fulfillment) and execution prowess (the first and only courier aggregator to sustainably service the budding market). We know this to be true, because existing participants are mired in persisting failures that didn’t improve until Shiprocket started transforming the market.

RTO is currently a fact of life. But as Shiprocket vertically integrates, RTO will be largely eliminated, causing an inflection point in how all participants experience e-commerce.

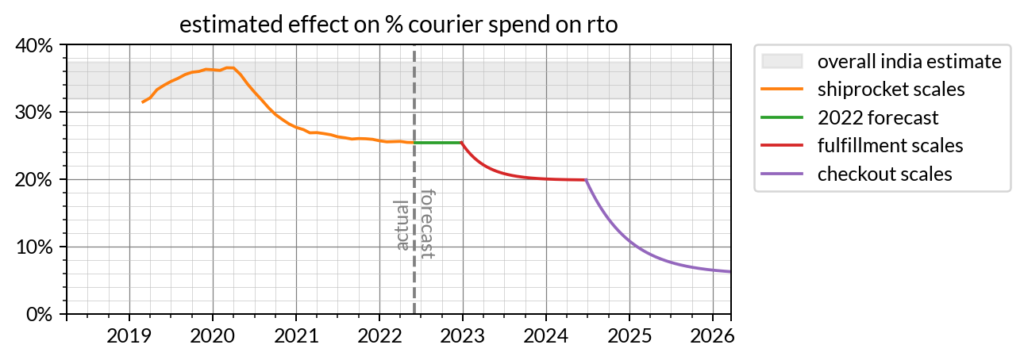

The greatest drivers of RTO are a) COD, b) last mile courier performance for hard-to-deliver packages and c) courier selection. Shiprocket has made a lot of progress on c) courier selection with their first engine of scale, visualized below with the realized reduction in fraction of spend on deliveries resulting in an RTO. With its next two engines of vertical integration, we believe that they will nearly eliminate the waste spend and poor all-around RTO experience for couriers, consumers and merchants.

As Shiprocket scales their fulfillment operation, we believe that in addition to margin expansion that Shiprocket can pass on to merchants, courier last-mile performance will improve and RTO waste will be driven down, visualized in the red line below. Finally, our estimates of a subsequent launch of a completely integrated Shiprocket checkout experience will finalize the inflection point where RTO goes from being a fact of life to a forgotten artifact.

- For a deeper discussion of how Shiprocket reduced RTO during the “Shiprocket scales” phase please see the FAQ

Shiprocket can become the gateway between its N-of-1 ecosystem and the capital markets.

Shiprocket has taken a two-pronged approach to building a large balance sheet:

- Operate profitably and efficiently

- Raise capital to fund expansion

Operating efficiently and raising vast quantities of capital at the same time is particularly challenging because usually there is a significant trade off between growth and efficiency. With such a balance sheet, Shiprocket can begin to unlock other tiers of capital markets like large debt facilities, a particularly challenging task in India.

- Merchant acceleration: Providing working capital to merchants and other forms of merchant enablement. This bottleneck alleviates a lot of the pain from RTO as well, where inventory lock ups, for example, are mitigated.

- Consumer acceleration: Directly underwriting and providing consumer credit and financing for larger purchases. Prepayment and other enablement will also greatly mitigate the RTO rate since it will eliminate a large driver – consumers changing their minds about a purchase.

- Ecosystem participant (banks, couriers, payment processors, 3PL, fulfillment partners, etc.) acceleration: A two-way channel to distribute capital into Shiprocket’s ecosystem for yield, and access that capital to service the ecosystem. For example, if Shiprocket is running a fulfillment partnership without owning the underlying assets, it can provide working capital and financing for the fulfillment operation to optimize and re-tool for MSMEs if needed.

Most merchants and consumers lack credit history and access to credit, and because of this are very challenging to underwrite. As the epicenter of its own ecosystem, Shiprocket has visibility into business operations, purchasing habits and RTO incidence rates that would uniquely position them to break this stalemate.

That is, Shiprocket can redirect the benefits of the capital markets to all of the participants in their orbit and accelerate the formation of a new e-commerce ecosystem, and in doing so, Shiprocket will become that ecosystem’s central utility.

In closing…

Shiprocket has found a path to unlock a new ecosystem for merchants and consumers to transact by leveraging unique developments in the Indian market, such as social media as a place of business, to bootstrap and scale a valuable payments and logistics infrastructure.

Shiprocket’s path to capturing the Indian E-commerce Transaction was the outcome of bottoms-up iteration and experimentation. In hindsight, solving fragmented shipping was not widely obvious and might even defy logic in the context of some of the other great e-commerce outcomes (Shopify, Amazon, etc). Conversely, such a counterintuitive insight is a required signature for an N-of-1 outcome.

The path to continued capture and expansion requires vertically integrating to build a unified ecosystem for all participants in e-commerce transactions and the supply chain. Together, this makes Shiprocket’s opportunity in India extreme. Another engine of unbounded upside might exist if Shiprocket becomes the gateway to unleash capital markets within Indian e-commerce.

Combined, this is why we think Shiprocket is an N-of-1 company – with the potential to grow by one or possibly two orders of magnitude.

Having underwritten thousands of varying degrees of product-market fit among the entrepreneurs we work with and invest in, occasionally a signature so strong emerges that not only has the opportunity to be a great outcome in an existing ecosystem, but instead has the potential to create a new market.

It’s been a pleasure and a humbling learning experience to partner with Shiprocket, and we share their vision of a future with unbounded possibilities.

– Tribe Capital team

To learn more about Shiprocket, N-of-1 and atomic units, please view our FAQ below.

We’re a venture capital firm focused on recognizing and amplifying early stage product-market fit. Reach us at hello@tribecap.co.

FAQ

How were you introduced to Shiprocket and were N-of-1 attributes present then?

We were introduced to Shiprocket through connections to investors in the original platform Kartrocket. Our approach is to analyze product market fit before doing broader diligence on the team or market.

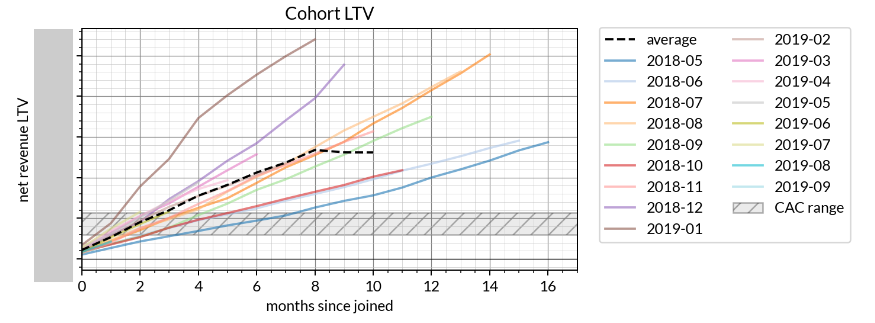

One of the early signals that Shiprocket might have N-of-1 properties was top-decile engagement and unit economics. We show the net revenue LTV (or the revenue earned by Shiprocket net of courier cost) from 2019 below. What this shows is that cohorts were breaking even in 2-6 months and sticking around for years. We see this by comparing the CAC (customer acquisition cost) band to the average cumulative net revenue over each cohort’s lifecycle, though we have obscured the exact scale of these figures.

This was a strong sign that not only had Shiprocket found product-market fit, but they would be able to efficiently scale. Pursuing this problem in more depth, we came to a number of realizations about Shiprocket and their market:

- The market segmentation did not mirror the e-commerce segmentation we were familiar with in the U.S. which prompted us to understand merchant behavior

- Execution was not a trivial composition of off the shelf tools, it required incredible focus, skill, market knowledge, negotiation skills and a vertically integrated stack to service merchants and earn a premium over what it costs to pay couriers to complete the shipment.

- The shipping product was the nucleus of an ecosystem rather than a terminal state

One figure that encapsulates this market insight is from their original deck below, and one factor that stands out is “Social Sellers”. This counterintuitive market segment demonstrates that product-market fit was in fact strong, and the nature of the market was unlike what solutions that mimicked those in the U.S. could service.

Shiprocket was our first Indian investment, and helped us realize the long-term promise of the Indian startup ecosystem.

What are the different ways in which Shiprocket supports the entire Indian e-commerce transaction?

One of Shiprocket’s key insights was that, while many products are serving Indian e-commerce merchants in everything leading up the purchase, the main pain points occur after the transaction has been completed; they call this “downstream enablement.”

The first step downstream of purchase is selecting a courier. Shiprocket gives MSMEs access to tens of couriers, who would otherwise not be interested in small merchants, and gives them the favorable negotiating terms of a large counterparty. The company also manages load balance between multiple couriers to ensure resilience, something which individual MSMEs wouldn’t have the time or capacity to do. Most importantly, Shiprocket selects which couriers would be best for a given delivery, which helps optimize delivery performance against cost.

Once a courier is selected and paid, Shiprocket enables fulfillment. Shiprocket’s network of leased warehouses across India does the picking, packing, and handling across hundreds of thousands of SKUs. Managing fulfillment also entails managing inventory; Shiprocket optimizes for where certain inventory should be in order to minimize delivery times (a crucial decision factor for most purchases).

The game isn’t over once the package is sent; managing shipping is replete with challenges. Courier and merchants have imperfect information and sometimes opposing incentives, and Shiprocket acts as a neutral party to make the entire process run smoothly. For instance, disagreements often arise about shipping weight, delivery timelines, or whether a delivery was actually attempted; Shiprocket’s data can help ensure that the right party is held responsible. This allows both parties to proceed in the transaction with confidence.

Beyond shipping, there is a long tail of customer needs including returns, cancellations, exchanges, and refunds. The complexities of a normal delivery are amplified in these cases, but so too is the payoff: happier customers lead to deeper loyalty. As Shiprocket continues to introduce products that further deepen downstream enablement, they become a partner in delivering customer loyalty to merchants. Through physical innovations in logistics and shipping, Shiprocket is acquiring trust and loyalty from consumers and merchants, which are becoming an important part of their competitive advantage.

Isn’t it a little early to declare Shiprocket the winner? Don’t N-of-1 markets attract fierce competition?

One challenge for pioneers is that product innovations are easier to copy than to invent, so a fast follower can get to the same scale with less wandering in the desert. The pioneer only has a head start, and must accelerate quickly to an “escape velocity” beyond which even a non-superior product can continue to hold the market for a long time. At that point, economies of scale, brand recognition, a host of other incumbent advantages become very powerful. In the case of Shiprocket, we observe this quantitatively in the company’s significant market share of Indian e-commerce. From a qualitative perspective, Shiprocket has become the default handler of Indian e-commerce and a household name in India.

Competition inevitably emerges, but the sheer gravity of an N-of-1 company pushes competition down one of two paths: they are shunted off into complementary parts of the ecosystem, or they are assimilated into the company. The best example of assimilation is the recent majority acquisition of Pickrr, a similar logistics and shipping enabler. But it is one of many other courier aggregators that have emerged in the years, including Vamaship, e-Courier, and Rocketbox. Most of these have remained tiny, and those that challenged Shiprocket meaningfully had to spend unsustainably into failure. Although Shiprocket didn’t formally acquire these companies, it did sweep up most of their former customers. This story hasn’t played out entirely, but each passing quarter makes it harder to challenge the now-recognized incumbent.

What about Amazon?

Amazon recently announced its intention to facilitate $20bn of Indian exports by 2025, and we expect that the company will continue to invest in the Indian e-commerce ecosystem. What does this mean for Shiprocket? It’s worth noting that, while Amazon is an N-of-1 company, it isn’t the only dominant company in North American e-commerce. Amazon’s relationship to Shopify is instructive; while the two compete on some market segments, they each have clearly-defined areas of excellence and concentration. Shopify dominates its core customer base of DTC brands who acquire customers through search and social media; Amazon dominates a different (larger) category of FBA sellers and customers who interact with Amazon directly. Accordingly, Shopify’s core technology is design, point of sale and marketing; Amazon’s core competencies lie in fulfillment and logistics.

In a similar way, we expect that Amazon and Shiprocket will occupy adjacent market positions in India. Amazon’s marketplace serves larger retailers selling commodity products, which benefit most from Amazon’s excellence in fulfillment. Shiprocket’s core MSME customer segment is somewhat different and is focused on D2C and social sellers. Some of the differences include heavy Whatsapp usage, higher rates of COD payments, and the desire to connect with customers without intermediary. As a result, these customers demand high performance among the idiosyncrasies of the Indian e-commerce market, and the Amazon model simply doesn’t work for them. Interestingly, some of Amazon India’s sellers already use Shiprocket’s Amazon integrations for shipping and fulfillment, such as for products with high rates of COD payments.

As the exact boundary between the companies’ core markets is drawn, we expect regulation to play in Shiprocket’s favor. There are two underlying political realities that are likely to aid Shiprocket. First, MSMEs are the backbone of the Indian economy and an important part of the way of life. As such, Shiprocket’s approach to supporting MSMEs as truly independent businesses should play well in regulators’ minds. Second, Indian authorities are more favorable to homegrown competitors, preferring to have control and ownership of important assets at home. Both of these have materialized in the fact that Amazon’s first-party model (managing inventory, fulfillment, etc.) cannot legally be controlled by a foreign entity like Amazon, according to the Bernstein Amazon India research report released in 2022. Authorities won’t decide the fate of Shiprocket, but they are likely to shift the playing field in favor of companies that align with these principles.

Can you go into more detail about RTO and how Shiprocket has reduced it?

RTO (return upon failed delivery) is one of the major factors holding back the Indian e-commerce industry. With around 20% of India e-commerce deliveries failing, RTO has become an accepted fact of life. Furthermore, it’s systematically entrenched: couriers are paid for both forward and reverse shipping, so a failed delivery actually generates more revenue than a successful delivery. As a result, couriers are not incentivized to solve systematic problems driving RTO. (This lack of alignment is also an argument for why it is unlikely for shippers to integrate upwards.) And Indian MSMEs are far too fragmented to create any kind of systematic change or even represent their own interests.

In our experience, creating a new market often hinges on providing a fundamentally different participant experience; Shiprocket is in the early stages of doing this by eliminating RTO. Shiprocket’s core product measures and manages courier performance, which shifts volumes towards higher-performing couriers. This creates a competitive incentive for couriers to lower RTO on Shiprocket-managed orders, which is a huge selling point for MSMEs.

As an example of how Shiprocket is tuned for Indian e-commerce specifically, the company has become the expert on Cash-on-Delivery (COD) payments. The fact that COD accounts for nearly half of deliveries is a quirk of Indian e-commerce that creates idiosyncratic challenges. With COD orders, the customer doesn’t suffer much for a failed delivery; they have no skin in the game. Furthermore, a failed COD order is not only increased shipping expense, but revenue foregone. It’s also a bigger challenge to manage cash flow and accounting under COD orders. Shiprocket’s COD payment management and remittance system solves many of these pain points by making payment expectations consistent, reliable, and predictable.

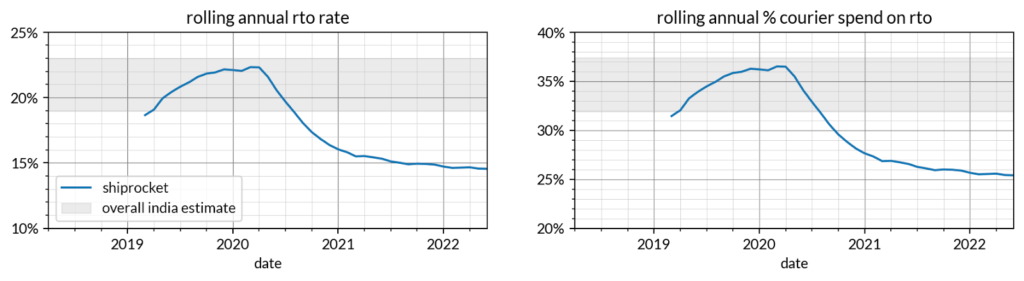

Below we show the progress that Shiprocket has made on the trailing 12 month RTO rate. Notice 3 periods:

- 2019-2020: Growth of MSMEs. Shiprocket’s first customer segment was Enterprise – where at the time, the prevailing wisdom was this was the only viable segment. But when Shiprocket first found product-market fit, they found it among MSMEs and smaller merchants. These merchants tended to receive higher rates of Cash on Delivery, as well as were some of the most challenging customers to service regarding tracking and returns. Hence this product-market fit manifested an artificial increase in RTO.

- 2020-2021: COVID drives prepay adoption. During COVID, among Shiprocket’s end consumers, more adopted prepayment, driving down RTO. Some of this was driven by macro factors, but other attribution goes to Shiprocket for educating their MSME merchant base.

- 2021-Present: Shiprocket drives continued RTO improvement through a data advantage. About half of RTO attribution is due to courier selection and last mile performance. Shiprocket has continued to improve RTO rates through their routing platform, a unique improvement which cannot be achieved pan-India with a single courier, or even a network of couriers, absent the scale and broad adoption in all corners of e-commerce that Shiprocket has achieved.

The gray band in the charts below indicates the best estimate for the RTO rates in India – roughly 20%. Some report that the broad RTO rate is as high as 30% in some regions and Tier 3-4 cities.

Also, the chart on the right indicates the percentage of payments to couriers that result in no package delivered. Because the merchant pays round trip for RTOs, this figure is significantly higher than the RTO rate. The general figure is that about 35% of all payments to couriers result in an RTO, as compared to 25% (and dropping) for Shiprocket.

It is crucial to note that even when accounting for prepay adoption, which we can even argue Shiprocket helped drive, and looking at just COD customers, we still see a drop of RTO rates in excess of 5%.

Why are there so few new N-of-1 companies outside of the US? What can we learn from this?

N-of-1 companies are not new to the 21st century, but the zero marginal cost of digital goods creates natural advantages of scale that are fertile ground for breakout companies. In the last two decades, such companies have overwhelmingly emerged from the US (think: Google, Apple, Microsoft, …), with the exception of the Chinese tech giants Baidu, Alibaba, Tencent and Xiaomi.

The success of Silicon Valley is often attributed to a network effect between early risk-seeking capital (i.e. VCs) and entrepreneurs, but this understates the importance of a robust market for liquidity from America’s unparalleled finance industry. In short, without private equity, corporate acquirers, and mature public markets, there isn’t sufficient reward to justify the risk of early stage and growth capital. In much of the global south, networks of entrepreneurs and early capital have sprung up, but attracting late-stage financing and security ultimate liquidity have remained big challenges for aspiring N-of-1 companies. Conversely, Europe has sufficient financial power for liquidity but has struggled to incubate sufficient entrepreneurial activity. The exception is the emergence of tech giants in China, which had both a strong entrepreneurial ecosystem and billions in early stage funding, as well as access to global financial markets and a relatively robust system of finance within China. We can see the importance of these financing networks in real-time; recent restrictions on access to global financing have already caused a sharp contraction of early capital in China.

One lesson is that N-of-1 companies need a realistic funding and exit plan as much as they need early product-market fit and an N-of-1 characteristic. For instance, one key consideration in underwriting companies in LatAm is the continuing ability of these companies to access broader financing markets. The successful IPOs of LatAm champions NuBank, Mercado Libre, dLocal, and others is encouraging, and it creates a valuable comp set for a next generation of IPOs. In addition to these companies, many still-private companies have raised hundreds of millions of dollars in globally-based growth capital, such as Rappi and Clip. Early-stage investors should stay attuned to what is happening in downstream financing, and the availability of exit capital should be understood separately for each investing geography.

A Brief Primer on Tribe Capital’s N-of-1 Theory: Recognizing the Scope and Scale of Companies Creating New Central Utilities

An N-of-1 company is one that identifies and captures an opportunity so large, a new market is created and the company is the central utility facilitating this new ecosystem. One example of this is Shopify, which created an SMB e-commerce ecosystem for developed markets where sellers have full agency over their brand and a vertically integrated software, payments and logistics suite to express it. Another is Snowflake, which developed an ecosystem around enterprise multi-cloud data warehouses.

Recapping our original exposition of N-of-1 companies, from our experience investing, operating and studying history, we have identified the following signatures of an N-of-1 outcome:

- Emergence of a new atomic unit of value — Eras present raw “resources” (oil, idle cars/gig workers, friend graph, etc.) that when captured, catalyze an immense wave of innovation within a sector. These might appear obvious in hindsight, but identifying them in the moment is extremely challenging, and usually involves an organic bottoms-up approach that does not anchor to existing products or markets.

- Capture of this atomic unit of value — N-of-1 companies translate their early foothold into a dominant position to acquire the newly viable atomic unit as fast as possible. Capture can be cemented by things such as network effects or economies of scale, but these tend to be the result of an N-of-1, not the path to one. The path more commonly involves vertical integration to build the ecosystem and market around a new atomic unit of value, because existing infrastructure tends to serve the need poorly.

- Transformation into a central utility — With dominance and control of the atomic unit, the N-of-1 company is able to rapidly extend its family of products around its ecosystem.

In terms of identifying the atomic unit, when we say “bottoms up” we mean the converse to approaching a market with a predetermined business model. It is the process of iteration, trial and error, and experimentation that allows the market to tell you where latent value is. For example, equity in private companies was already managed by expensive service providers, but Carta offered cap tables for free and used that as a wedge to re-architect equity and liquidity in private markets. Top-down approaches to managing equity would largely revolve around charging for cap table management, until Carta proved otherwise.

Vertical integration is the lever to scale and completely dominate the atomic unit. You construct the infrastructure for the new market, placing yourself at the epicenter, and in doing so are able to capture 100% of the value generated by the atomic unit. Note that this is not to avoid a battle for margin with the supply chain, but simply due to the fact that oftentimes no supply chain even exists, particularly if the market and ecosystem itself do not exist until the N-of-1 company creates it.

Emerging markets also present unique opportunities for N-of-1 outcomes. While there have not been many N-of-1 outcomes outside of the US so far, we believe that emerging markets will present opportunities for abundant new atomic units. This is because market idiosyncrasies prevent known solutions in developed markets from translating.

Legal Notices

Any unauthorized copying, disclosure, or distribution of the material in this article is strictly forbidden without the express written consent of Tribe Capital Management LLC (“Tribe Capital”).

This document is for informational purposes only and is not intended as investment advice, an offer, or solicitation with respect to the purchase or sale of any security.

Certain information presented herein has been supplied by third parties, including management or agents of the underlying portfolio company. While Tribe believes such information to be accurate, it has relied upon such third parties to provide accurate information and has not independently verified such information.

This document contains forward-looking statements. The opinions, forecasts, projections, or other statements, other than statements of historical fact, are forward-looking statements. Forward-looking statements can be identified by the use of words such as “anticipate,” “intend,” “believe,” “estimate,” “plan,” “seek,” “project,” “expect,” “may,” “will,” “would,” “could” or “should,” the negative of these terms or other comparable terminology. Examples of forward-looking statements include statements relating to macroeconomic conditions, expectations regarding future growth, including future revenue and earnings increases, margins, free cash flow projections, and annual growth rates; growth plans and opportunities, including our strategies for future or potential acquisitions, product expansion, targets, and geographic expansion; estimated returns on in future; and assumptions underlying these expectations. Actual events or results or the actual performance may differ materially from those reflected or contemplated in such statements.

Nothing contained in this presentation may be relied upon as a guarantee, promise, assurance, or a representation as to the future. These statements have not been reviewed by anyone outside of Tribe Capital and while Tribe Capital believes these statements are reasonable, they do involve a number of assumptions, risks, and uncertainties.

The graphs, charts, and other visual aids are provided for informational purposes only.

TRIBE CAPITAL® and certain other marks or logos displayed on this presentation are registered trademarks and service marks of and owned by Tribe Capital. You may not use any of those or any other Tribe Capital trademarks, trade names or service marks in any manner that creates the impression that such names and marks belong to or are associated with you or your affiliates or are used with Tribe Capital’s consent.