Nothing lasts forever — not even unicorns. But some unicorns live long lives.

The life cycle of consumer products is depressingly predictable. A product becomes a hit because it resonates with a generation. And as time goes on, that generation matures and is inevitably replaced by a fresh set of customers with distinct tastes and perspectives. The product, a victim of its own success, eventually hits a ceiling.

In technology, the cycle is on constant repeat. Once a consumer product starts to gain a large audience — it risks disruption from another new solution, one that ups the innovation ante. These usurpers then grow and are themselves eventually displaced. That’s the classic pattern of disruption — what Clay Christensen calls the Innovator’s Dilemma.

I’ve had the privilege to witness this cycle thousands of times. After building and growing many Facebook apps, games and mobile apps, I’ve learned that once a product finds or gains a large initial audience, there are two options for achieving large scale growth:

- The product evolves and becomes a platform that other companies can integrate into their own products, building specialized use cases for their audience. Facebook launched its platform in 2007 and grew its monthly active users from 50 million to 1.44 billion, a 28.8x increase.

- The company decides to try and disrupt its own product. Deliberate disruption helps fight off all the other companies (usually startups) who are going after the audience. Apple has created innovative products, such as the iPad, in order to fuel its own growth. One might imagine that the iPad has the potential to take market away from Apple’s own existing products (i.e. Macbook).

Often times, both of these things happen. As a result, a consumer eventually gets used to a feature and the shiny new product loses its appeal. Then, something new and novel comes along and the cycle of disruption starts again. For a company to survive long-term, it must own whatever disruptive thing comes next.

Disruption is The Only Choice

Recently, designer Ben Barry shared a few pages from Facebook’s Little Red Book, in which he explained how consumer companies have successfully innovated to stay relevant.

“If we don’t create the thing that kills Facebook, someone else will.”

In plain english (no MBA required), this statement explains what’s required to innovate and grow with a large existing audience. Sustainable growth comes from aggressively seeking to kill your cash cow before someone else does. Companies tend to protect what they have instead of trying to destroy it themselves through innovation. Consumer businesses that are willing to cannibalize their existing audience are the ones that can survive in the long-term.

Steve Jobs knew this and Apple’s continuous growth can be attributed to the strategy of cannibalizing an existing audience.

Why Successful Companies Struggle With Innovation

Inevitably, once there’s a large audience, companies have to disrupt themselves through innovation or they will be victims of their own success.

That’s the classic Innovator’s Dilemma.

Clay Christenson’s work isn’t exactly a secret. Yet consumer companies get disrupted time over time because of the powerful inertia that occurs within the cocoon of success. Inside that cocoon, three common beliefs take hold:

- Companies think their existing audience will come over to any new product they create.

- They assume that the intent of a user can be suited or modified towards any new offering.

- They believe they can monetize with their existing business model.

On the surface these beliefs sound harmless; however, they are as toxic as curare. They lure companies into thinking that their mission is to protect their existing audience — a deadly mistake. Each consumer product has an audience who signed up with the intent of its specific use case or service. This makes it ineffective to try and get a large percentage of an existing audience over to a new product or service that has a unique intent.

Many Growing Companies Lose Sight of Innovation

As companies grow, they hire people to handle the demands of that growth, both to deal and to cope with a larger internal organization. This often leads to a culture of scaling over a culture of innovation. Here’s what commonly happens:

- The organization breaks into functional silos. Product, sales, marketing, customer support and finance all become their own departments. Some companies try unique ways of working to avoid the pitfalls of silos.

- Ideas, people and things start to separate and spread across floors, buildings, and geographies. People now sit physically far from each other. Their internal culture becomes fragmented.

- Individual team members get more singularly focused on the problems in their own departments. The organization gets better at improving the existing product for its current audience and intent.

Each team begins to work on separate parts of the product. Piece by piece, the app goes from being owned by an entire company to being the responsibility of siloed teams. While this allows for the company to solve for the behavior of its existing audience, and these changes serve the company functionally as it scales, they ultimately lead to an environment that’s less innovative.

Solution One: A Family of Brands

It’s hard to innovate on a single, massively popular product. So, successful consumer companies often end up with new ones in addition to their flagship efforts. This transformation from a single product to a family of products occurs when a consumer business reaches a saturation point for its market. With most free consumer products, you see the transformation when the initial core product starts reaching the masses of hundreds of millions of people, or in Facebook’s case, an amazing 1.44 billion monthly active users as of March, 2015. Members of the family may come from acquisition (sometimes a “defensive play”, working to end a threat from a potential disruptor) or internal efforts. In any case, consumer companies end up with a family of product brands, each serving as a family member with different audience intent.

The family of brands strategy is what P&G has used to survive for the last 177 years. And it’s working. Their 2014 revenue was $83.06 billion.

P&G has 23 brands with annual sales of $1 billion to more than $10 billion, and 14 with sales of $500 million to $1 billion — many of those with billion-dollar potential.

Some of those products compete with each other, and that’s fine. It’s better (and cheaper) to constantly try to cannibalize your existing business with your own new brand than be disrupted by another company that’s more nimble and growing more quickly.

P&G’s brand explosion isn’t surprising because it competes with rivals for space on supermarket shelves. More unexpected is Facebook’s approach — which is similar. It has a huge audience, yet the company understands that consumer businesses with massive existing audiences can’t simply transfer their original audience to new products.

Thus Facebook did not integrate Instagram after it bought the company in 2012. It also operates WhatsApp independently. A year earlier it made Messenger a standalone app, and more recently forced mobile customers to adopt it by excluding messaging from its main app. Now, over three years later, Messenger might be starting its own little family. It its 2015 F8 conference, Mark Zuckerberg formally announced their strategy as the Facebook Family of Apps.

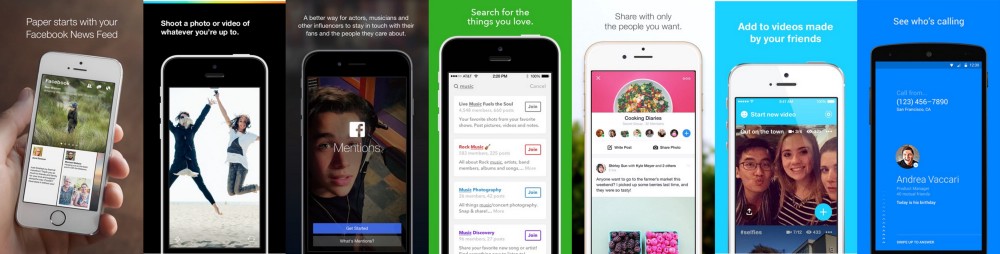

Facebook Family of Apps 2015 F8

Each member of the family has the potential for over a billion monthly active users (people). Instead of one platform under perpetual attack, Facebook has five, each one still innovating.

They’ve even released at least seven products as part of Facebook Creative Labs. Most are new brands too! These new products represent the company’s aggressive efforts on trying to discover the next big thing.

Facebook’s Creative Labs Apps

Not all of those apps succeed — but they don’t have to. Facebook uses them to test new innovations that might find their way into the larger products. Just developing those apps keeps edgy innovation alive at Facebook’s headquarters at One Hacker Way.

P&G and Facebook are not alone in thinking about cannibalizing their existing products with new brands. Amazon, Apple and Netflix also execute with similar strategies.

Solution Two: Don’t Be Afraid to Eat Your Own Products

In his biography, Steve Jobs said it bluntly:

If you don’t cannibalize yourself, someone else will.

And in Apple’s Q1 2013 earnings report, CEO Tim Cook elaborated:

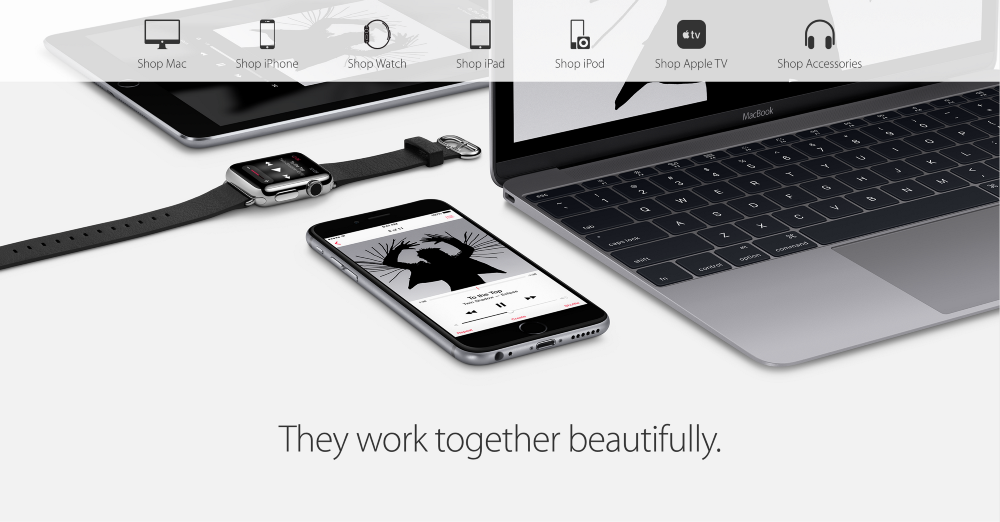

Our core philosophy is to never fear cannibalization. If we don’t do it, someone else will. We know that iPhone has cannibalized some of our iPod business. That doesn’t worry us. We know that iPad will cannibalize some Macs. But that’s not a concern. On iPad in particular, we have the mother of all opportunities because the Windows market is much, much larger than the Mac market. It is clear that it is already cannibalizing some. I still believe the tablet market will be larger than the PC market at some point. You can see by the growth in tablets and pressure on PCs that those lines are beginning to converge.

Header from Apple’s US online store.

Apple has an added advantage: an increasing number of people own more than one Apple device. Apple grows their business by creating new innovative products that work exceptionally well with your existing Apple products. Their strategy is to cannibalize their own products by creating new products that fulfill some of the same consumer needs as the existing ones.

Amazon Kindle. Photo: Andy Ihnatko via Flickr.

Another giant technology company, Amazon, has continually cannibalized its audience, beginning with its transition from being a physical goods focused company to a digital one. Consider the Kindle: a device that became home to the world’s biggest bookstore, and lured people away from buying physical books. If Amazon didn’t do it, someone else would have. Amazon succeeded with the Kindle by having a maniacal focus on reducing the costs and increasing the speed of delivery. It was a good way to keep innovation central to Amazon — because pioneering a new product category forced innovation.

Amazon is also a big time participant in the Family of Brands approach. Many of it’s 40+ subsidiaries are separate brands where Amazon’s branding is kept to a minimum. These include Zappos.com, Diapers.cm, audible.com, IMDb.com Woot.com, Fabric.com, Soap.com, Pets.com and many more.

Amazon’s innovative strategy of cannibalization and creating a family of brands is working. In 2014 revenue was $88.99 billion — several billion more than P&G. Not bad for a company that’s only 21 years old!

Of course, these strategies are risky. Netflix is perhaps the most striking example of a company that balances the risks as well as the rewards. First, Netflix successfully shifted its core business from a company that shipped DVDs to people’s home into a streaming media service that works on all of your devices. The result was a paltry auction sale of the incumbent, Blockbuster.

By September of 2011, the transition was made, and Netflix made its strategic play at being a family of brands. Netflix attempted to split up the one brand into two by spinning out the DVD rental business into a new brand. It was called Qwikster.

Source: https://www.flickr.com/photos/methodshop/6166107840/

It was a disaster, in part because of pricing and in part because its customers simply hated the idea. Netflix CEO Reed Hastings was smart enough to change course; not only did he reverse the decision but he made a public apology to customers.

Netflix’s real failure at that time was that its new brand wasn’t really an advance: both its old and new brands were about delivering content. But the entertainment business — where Netflix wanted to be — is about the content. Hollywood studios and television networks regard delivery mechanisms as a commodity. But, Netflix realizes, when you have a hit, you own a monopoly on it. People have to come to you. Netflix disrupted its industry by creating the easiest way to watch TV shows and movies online, taking away the opportunity for the entertainment industry to build brands around content and speak to particular audiences through a unique value proposition. For this vertical, the family strategy has historically been all about content. The strategy treats the delivery mechanism (DVDs in the mail or streaming over the Internet) as a commodity.

Initially, Netflix didn’t own the content they distributed. While the strategy was instrumental to its creation of a successful platform business, the winning strategy for Netflix was to imitate what’s worked for the networks. Networks such as HBO cannibalize their own existing entertainment content with fresh new content. They’ve gotten great at it and the strategy works well for the entertainment industry. Just like in gaming where you’re always trying to create the new hit game, you end up needing to always find the new hit TV series. Each new series becomes a member of your family.

And that’s what Netflix did starting slowly with the release of House of Cardsin February of 2013 and then accelerating dramatically. They’ve since released about a hundred original programs and it appears that its formula for growth is working. The release of House of Cards Season 1 also started the climb of their stock price from $160 to over $600 (before an upcoming 7 for 1 split). Having passed through the want phase of the consumer product life cycle, now Netflix is in the need phase where it must keep existing customers and attract more. At the risk of upsetting their content partners, they’ve evolved their business to produce their own content, and changed their existing business into an engine of cannibalization.

$NFLX

Because of Netflix’s success, every way that consumers watch video will eventually support binge watching of new seasons. An important lesson from Netflix’s journey is that the family of brands strategy needs to be tailored to both your consumers and your vertical.

Who are the next companies to grow families of brands?

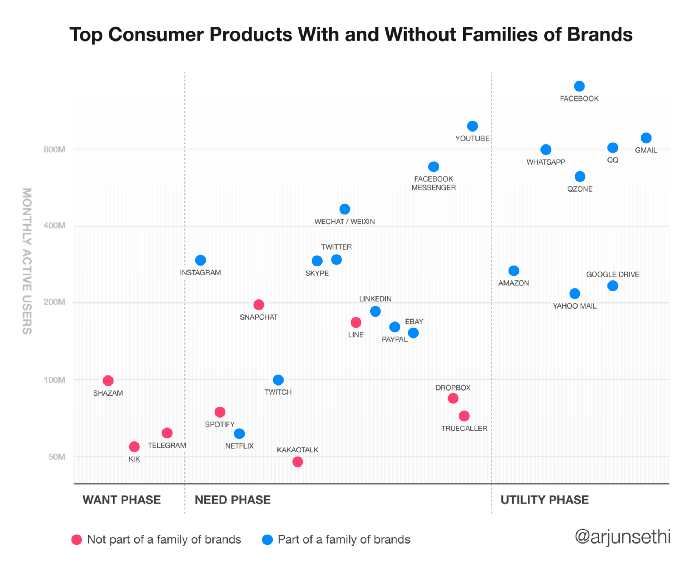

Smart founders and CEO’s have not missed the importance of these lessons. It is a common strategy to use cannibalization and families of brands to stave off the Innovator’s Dilemma. The evidence is below: a chart of 26 major companies, many of which are sited within a family of brands. Logic dictates that the others will soon follow:

Consumer Products With Large Audiences

Out of these major Internet powers, 18 (the blue dots) have already begun their family of brands. The remaining eight (pink dots) do not have a growing family of brands yet. Out of those eight, Kik, Shazam and Telegram are still in the want phase of their life cycle. These companies should be focused on doubling down on their core value proposition while continuing to grow. But once a product reaches the need phase, it’s time to think about a strategy for ensuring long-term survival. The other 5 companies have all reached the need phase, Dropbox, KakaoTalk, Line, Snapchat and Spotify.

Of those Dropbox is furthest along moving towards becoming a utility. Dropbox is on the path to a family of brands. It has already created the Dropbox Platform and Dropbox for Business. It acquired Mailbox and created a photos app called Carousel. It also has a new product called Notesin beta. The Dropbox team is thinking about the future in the right way. They are evolving the product into a platform, getting larger customers, acquiring other products and trying to create new ones. It’s part of a cannibalization strategy that Steve Jobs would have found familiar.

The organizations that we will see turn into 100+ year old companies will be led by innovators who know that disrupting their own products is key to their survival and success, and that mentality will be reflected in their culture.

The Rules of Survival

It all boils down to a few rules, but if you need me to repeat them at this point, you may not be smart enough to run an Internet company. Nonetheless, here they are.

- Large audiences are hard to get and it takes time. Facebook’s been trying hard and it took them 8 years to get to 1 billion monthly active users.

- You must constantly try to disrupt yourself. The most successful companies embrace cannibalization at the core.

- You’ll eventually have a portfolio of products. Your own family of brands.

Here’s the thing about large audiences: by the time you get there, your user base becomes part of the last generation. You’ll start seeing competition from startups who are growing their audience faster than you were at their age. You need to innovate and be willing to threaten the core of your business in order to survive. Or you’ll die!

The final part of the quote in Facebook’s Red Book says it best:

“The internet is not a friendly place. Things that don’t stay relevant don’t even get the luxury of leaving ruins. They disappear.”

But they don’t have to.

Follow Backchannel: Twitter | Facebook

The thoughts in this essay are personal views and not those of my current employer. If you have thoughts about the ideas in this essay, please continue the conversation via the responses below. You can also contact me at @arjunsethi.

Special thanks, Evelyn Rusli, Josh Elman and Hiten Shah for reading drafts.