To the casual spectator, Facebook is having a terrible year. Besieged by privacy scandals, the company was torn into by Congress, the press, and the public alike. To make things worse, the founders of WhatsApp and Instagram left Facebook in what seems to be a complete rejection of the company.

The divide was so deep that WhatsApp co-founder and CEO Jan Koum forfeited up to $1.2 billion so he could leave the company last September—three years after selling his startup to Facebook for $19 billion. WhatsApp’s other cofounder, Brian Acton, left earlier this year, leaving $850 million in unvested options expire. Shortly after, he tweeted that he was deleting his Facebook account.

In an interview with Forbes, he said:

“At the end of the day, I sold my company. I sold my users’ privacy to a larger benefit. I made a choice and a compromise. And I live with that every day.”

Six years after Facebook acquired Instagram for $1 billion, this September Instagram cofounders Kevin Systrom and Mike Krieger also left the company.

While the press has taken these defections as a sign that Facebook’s time is over, the company has continued to exceed quarterly earnings expectations despite more difficult growth conditions. Facebook is doing just fine.

It’s not such a big deal that Koum, Acton, Systrom, and Krieger left Facebook. What’s astonishing is that they stayed so long in the first place.

Founders rarely stay at a company they’ve been acquired by for more than two years. Founders are headstrong, like to call the shots, and don’t bend easily to authority. Facebook managed to attract and retain a group of the most talented product people in the Valley for over four years. Not only that, but Facebook also adroitly integrated these companies to the point where Instagram served as a vital attack vector against the encroaching threat of Snapchat.

Facebook can survive a few people leaving because it built a strong platform around its people. During my time founding, running, scaling companies like Lolapps, Nexon, and MessageMe I went through the gauntlet of what worked and what didn’t by running teams on the ground. By investing in companies that are building great leadership and people platforms like Slack, Cover, Carta, and Front, I’ve continued to compound that knowledge. But more importantly, from my time at Yahoo and Social Capital, I’ve seen first hand what happens when a company doesn’t transform to have a platform for scaling and incentivizing people and talent. Things quickly fall apart.

Companies that want to survive the next 10 years build software platforms. Companies that want to survive beyond that build people platforms.

People Platforms

When a company is racing toward product-market fit and trying to scale their product to thousands or even millions of users, it reaches a turning point. If it wants to compound growth, it needs to transition from a single product team to a people platform that can support multiple teams.

A software platform works as an intermediary between a company’s products, users, and third-party developers, enabling new and surprising behavior. It creates an ecosystem that allows new products and services to be built at lower incremental costs.

A people platform extends and amplifies the capabilities of team members the way a software platform extends and amplifies the capabilities of its products.

Building a software platform allows you to extend the utility of a single product and save time, which allows you to stay ahead of the next innovation cycle.

Apple, for example, began by selling devices like the Mac and the iPhone. By creating a platform through the App Store, suddenly third-party developers were building new utilities for Apple’s customers — and even gave Apple a cut. Facebook began with an online directory for college students and a monolithic product with an advertising backend, and transitioned into a platform that it could plug new products and services into.

The same principle applies to building a platform for your team. When you’re first building a team, you’re working within a set of constraints. You have a fixed amount of cash in the bank and a timeline to create a product. You form a team around the attributes you need today rather than thinking about how you can extend your team tomorrow.

When you’re building a platform for your team, you’re parsing out the core functions of your company into an extensible architecture. You’re growing an ecosystem around your company and making it more valuable than the sum of its parts. That enables new behaviors to emerge between your people that allow you to save time and adapt to change.

Design Principles for Building a Platform for Your Team

Design principles are building blocks for your company that force clarity and reduce ambiguity by guiding behavior along a set of guidelines. With the right set of design principles, you can direct behavior along a path while allowing the creation of new patterns if legacy patterns aren’t working.

If you try to organize your company on the same model as a Google or an Amazon, you won’t actually build something that lasts. The pediatrician John Gall’s research into the development of children led him to a simple truth about systems:

A complex system that works is invariably found to have evolved from a simple system that worked. The inverse proposition also appears to be true:

A complex system designed from scratch never works and cannot be made to work. You have to start over, beginning with a working simple system.

Amazon’s decentralized, “two pizza” teams work because product teams have a core set of internal tools and APIs that the teams can plug into. Spotify’s “chapters” and “squads” org structure is built around developing a mobile music player and a web app. Trying to copy them blindly ignores the context of your own company.

To build a platform for your team, you have to start by understanding the dependencies between your team and why they exist. Rather than trying to impose a complex system, start with a set of design principles for building a platform so you can adapt and scale.

Doing so means loosening the reins and delegating key decision-making to team members on the ground rather than to founders. That requires taking a huge risk, because you’re ceding control over part of your company. But by designing core principles that drive behavior, you open up your platform to new and surprising innovation from the bottom up.

Here are four design principles that will allow you to build a platform for your team:

- Flatten the ladder. While hunting for external talent helps you fill immediate needs, you build a platform by growing leadership from the bottom up.

- Create clean interfaces and autonomy between teams. Instead of structuring the way a team operates, structure how the teams communicate and interface with one another, and allow them to execute autonomously.

- Burn the ships. Companies need the ability to internalize external changes, and that often means abandoning safety nets.

- Leave culture undetermined. Overdetermining culture creates process and bureaucracy. Instead, concrete and memorable values allow new and surprising behaviors to emerge from your team.

In the rest of this article, we’ll walk through each principle and show how to build a platform for your team.

1. Flatten the ladder.

Leaders aren’t born, they’re made. You may be able to grow your team incrementally by hiring a new engineering lead who’s better than a current engineer. But even a mediocre engineer who sticks around, compounds, and expands their role will overtake a Silicon Valley mercenary who jumps around from job to job.

Startups should spend less time looking for leadership to “fix” the company through external hires, and more time trying to create conditions that allow leadership to grow from within. That means flattening the ladder and providing upward mobility for your troops on the ground.

At times, you may need to hire an experienced COO or CFO to help scale. But filling every top rank with outsiders tells your team that there isn’t room for personal growth at your company.

“Hiring the best people” isn’t a sustainable long-term strategy. To build a platform for your team, you have to build leadership from the bottom up over the course of years — not quarters. Finding external talent is a short-term fix to fill immediate needs.

Talent is under your nose if you care to look for and invest in it. That’s the only way you can create a people platform.

By early 2002, as Google’s product line was expanding from Search, the company’s homegrown technology stack grew increasingly hard to navigate. While small teams at Google were developing new ideas all the time, deploying them into production was a different story.

Google needed product managers — people who understood Google’s web of infrastructure and software products and were able to steer new ideas across engineering, design, and marketing to production. The only problem was that these people didn’t exist. So instead of trying to hire external talent, Google flattened their organizational ladder and created internal talent.

Marissa Mayer, an early product manager at Google, bet a coworker that she could train new product managers faster than he could hire them. This training program was known as the “Associate Product Manager” (APM). APMs were sourced from recently graduated computer science majors for a two-year rotational position. Upon joining the company, they were assigned to a product, like Search or AdWords, for a year. The next year, they would rotate to a different department.

The APM program rapidly trained product managers by giving them real responsibility — the first APM was put in charge of Gmail — and cycling them through different products. Instead of just learning how to manage a single type of product, they were exposed to multiple sides of the business.

Graduates of Google’s APM program have not only filled dozens of senior leadership roles at the company but also constitute one of the most talented groups of product managers in the Valley.

Some former APMs include:

- Brian Rakowski: Worked on Chrome and Gmail. Currently VP of Product Management at Google.

- Wesley Chan: Worked on Google Toolbar, Google Analytics, and Google Voice. Currently Managing Director at Felicis Ventures.

- Bret Taylor: Worked on Google Maps before joining Facebook as CTO. Currently President and Chief Product Officer at Salesforce.

- Jeff Bartelma: Worked on product search at Google. Currently Director of Product at Dropbox.

- Clay Bavor: Worked on Gmail, Google Docs, Google Drive. Currently VP of VR at Google.

You know you’ve built a platform for your team when a large chunk of senior leadership started from the bottom of the company. As former Google CEO Eric Schmidt said: “The APM program is one of our core values — I’d like to think of one of them as the eventual CEO of the company.”

Microsoft

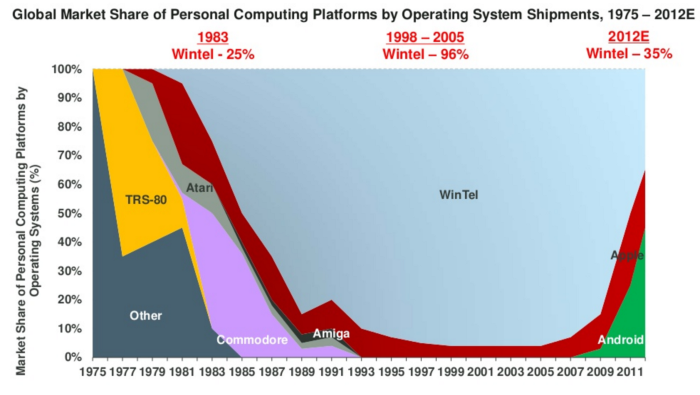

In 2000, Microsoft had a market cap of $510 billion, making it the most valuable company in the world. By 2012, that had fallen sharply to $249 billion. While many factors led to this decline, one of the most insidious was Microsoft’s infamous “stack ranking” system of evaluating performance and how it encouraged constant infighting within the company.

In a 7,000-word expose on the company, Kurt Eichenwald writes: “Every current and former Microsoft employee I interviewed — every one — cited stack ranking as the most destructive process inside of Microsoft.”

The way that stack ranking worked was simple: Employees were evaluated on a bell curve, which meant that for every team of employees, a predefined percentage had to be ranked as either top performers, good performers, below average, or poor. For any given team — no matter how well the team performed — at least one team member would be written off with a bad review. If you were a good developer, you were incentivized to work on teams with mediocre developers to artificially raise your rank.

One Microsoft engineer described the destructive behavior as follows:

People responsible for features will openly sabotage other people’s efforts. One of the most valuable things I learned was to give the appearance of being courteous while withholding just enough information from colleagues to ensure they didn’t get ahead of me on the rankings.

The problem with stack ranking is that it localizes performance within individual teams and products and makes it political. When the primary behavior at your organization is political, it stifles upward mobility because people who are in power seek to preserve their power.

As employees carved out fiefdoms within Microsoft from Microsoft Office to Xbox, they competed internally over incremental gains for existing products. In doing so, they were blindsided by external innovations like cloud computing and the iPhone.

2. Create clean interfaces and autonomy between teams.

As a company scales from a single product to a platform, it needs to transition from a single team to multiple teams piece by piece.

Teams should be loosely coupled. That means there are few dependencies between teams, and teams are able to move quickly and independently. If a product team building a new feature has to ask a sysadmin each time they want to deploy new code, a costly bottleneck is created, which slows down the iteration cycle.

Teams also need bounded contexts — the ability to communicate in a ubiquitous language without needing deep, domain-specific expertise. For example, if product and dev ops are both organizationally aligned with the need to launch features securely and have built a process for doing so, they don’t need to consult each other every time a new feature is built.

Enforcing these two principles allows teams to innovate independently while working toward a shared goal with a united front.

Amazon

I want people who are stubborn about their vision of creating something new and valuable. I want them to be relentless on their vision but very, very flexible on the details of how to get there.

Communication is a sign of dysfunction. It means people aren’t working together in a close, organic way. We should be trying to figure out a way for teams to communicate less with each other, not more.

Amazon is run with an emphasis on decentralization and independent decision-making. In practice, that leads to small teams that are run like individual startups within the broader company.

Amazon’s management philosophy can basically be summed up in two parts:

- More coordination wastes more time.

- The people closest to the problem are in the best position to solve it.

At Amazon, small teams of 6 to 10 people each have a mission and act autonomously to accomplish it in “two-pizza teams,” and they often are given budgets.

Early on at Amazon, each team was measured according to a single, key business metric called a “fitness function.” In a fulfillment center, a fitness function might involve decreasing costs related to packaging and shipping products. At Amazon Web Services, it might be uptime or revenue. This helped keep teams accountable while acting autonomously.

By loosely coupling teams and limiting interdependencies, teams can move faster. This leads to an organizational structure in which Amazon is run as multiple different startups within the platform of a broader business. Different business units can share resources and information, but they’re not dependent upon each other to move quickly and innovate.

The principle of Amazon’s management structure is that you can harness the complexity of the organization by breaking it down into the smallest individual parts: teams.

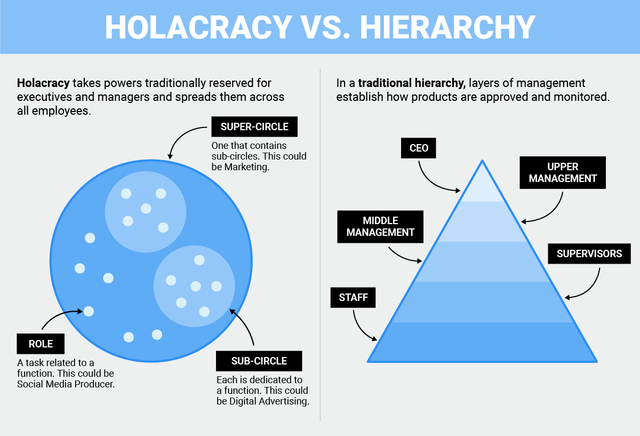

Zappos Holacracy

In 2013, Zappos CEO Tony Hsieh began advocating for a new management structure known as holacracy. Holacracy was meant to eliminate hierarchies at Zappos — but without hierarchies and clean rules, team members ended up spending five extra hours a week talking about how to organize and govern themselves. By creating new layers of management, the system required too much additional context for team members to process, slowing down their execution speed.

Under holacracy, team members determined their own jobs, self-organizing into “circles” around functions like customer service, engineering, and HR. While this was meant to eliminate management bureaucracy, in practice it meant that team members had to do their jobs while figuring out what their jobs were.

Instead of being assigned projects, they spent countless hours in “governance meetings” to decide roles and responsibilities, and in “tactical meetings” to track progress.

As a consultant advising Zappos on the holacracy rollout noted: “Asking [employees] to learn the management equivalent of Dungeons and Dragons on top of their workload is foolish, if not inhumane.” Simply eliminating management hierarchies does very little to dissolve human friction. One Zappos team member complained: “I’m afraid to speak up in my Circle because I’m afraid my lead link might retaliate.”

Holacracy, in some ways, is the logical outcome of a startup culture that’s focused on relentless optimization. But what people forget is that leadership revolves around managing emotional needs rather than ignoring them.

3. Burn the ships.

In the third century BC, a Chinese general named Xiang Yu sailed his troops across the Yellow River into enemy territory, where they faced overwhelming odds.

Another general may have tried to motivate his men through inspirational words or by promising them eternal glory and riches. Xian Yu did one better. He burned his men’s ships and smashed their cooking pots. That drastically narrowed the set of options facing his men: They could win or they could die. They won.

Evolution is a function of environmental change. An early-stage startup is in a constant state of crisis — the ships are always burning. This shortens the feedback cycle and allows a company to learn faster. As a company grows bigger, the threat of constant extinction disappears, making it harder to select the traits necessary for long-term survival. When a company has been around for a while, they have cash in the bank and a buffer against environmental change. But if they remain complacent, the world catches up and the company goes extinct.

They turn into dodos or dinosaurs, in a process that Darwin described in On the Origin of Species:

These anomalous forms may almost be called living fossils; they have endured to the present day, from having inhabited a confined area, and from having thus been exposed to less severe competition.

To build a platform for your team, you have to design for change, and often times that means setting your ships, or security blanket, on fire.

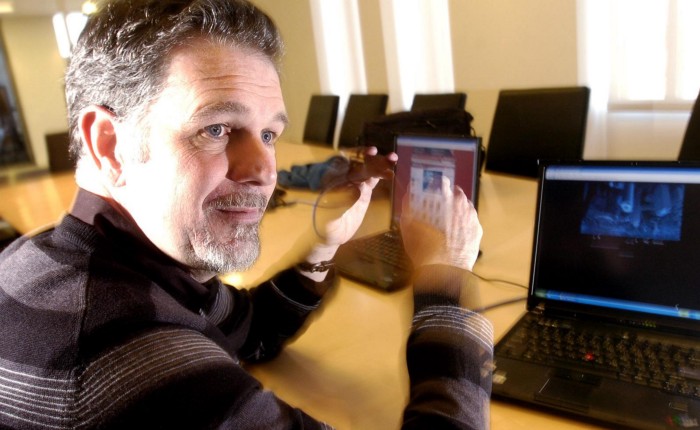

Netflix

Netflix spent a decade as a DVD-delivery business before they moved to streaming. To adapt to a streaming company, Netflix had to do the hard thing and burn their ships by sidelining the DVD business.

This began on a single day, when Reed Hastings banned every team member working on the DVD-delivery end of the business from executive staff meetings. At the time, 100% of Netflix’s revenue came from delivering DVDs. Hastings was essentially betting the future of the company on streaming, and doing it so explicitly that it left no room for interpretation.

The ultimate survival of Netflix depended on its ability to evolve into a streaming company — not its ability to spend more time growing a DVD business destined to shrink over time. While the DVD team at the company may have understood the logical reasoning behind this at the time, people instinctively stick to what they know. What they knew was that DVDs made money. So Hastings banned the team from executive meetings.

In doing so, he internalized an external change in the environment — the possibility of streaming — in a way that no one at Netflix could ignore. Today, Netflix has a dozen different competitors, from Hulu to Amazon Prime Video to Disney. If Netflix hadn’t been able to burn the ships, it’s very possible the company wouldn’t have moved fast enough to capture the market.

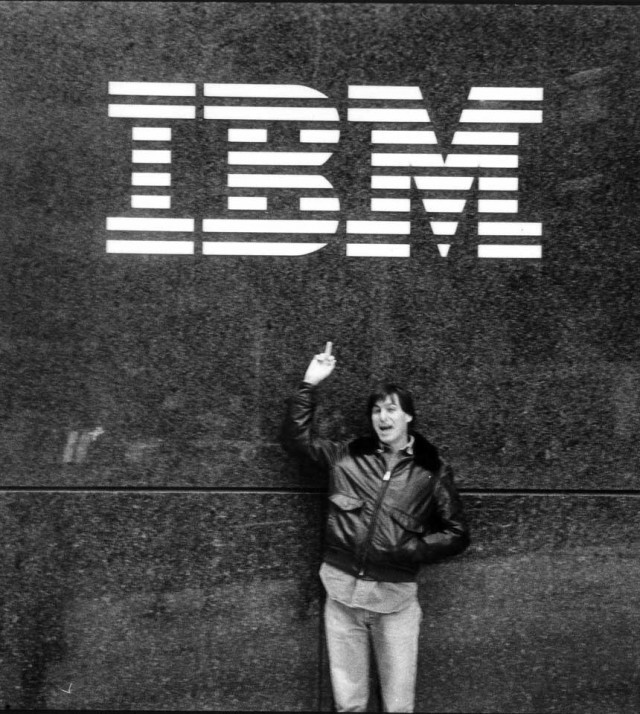

IBM

Without the ability to burn the ships and course-correct, even the most successful forfeit their hard-earned advantages and enter decline. Just look at IBM. By evaluating team members primarily on the basis of profit, IBM optimized for the short term and failed to internalize the longer-term potential for external change and disruption.

In the 1950s and ’60s, IBM was the most famous company in the world, having successfully transitioned from manufacturing tabulating machines to producing integrated mainframes.

But decades of success calcified into a bureaucratic management culture in which even small decisions required lengthy audits and endless processes. This approach of “playing it safe” served IBM well when it came to selling $20 million mainframes to large Fortune 500 companies in the mainframe business. But it unwittingly created a top-down management culture that stifled decision-making with red tape.

This led to the company’s near extinction with the rise of the personal computer. Even though IBM developed one of the first PCs, the company’s management was run by people used to selling mainframes. Instead of burning their ships, they overextended the mainframe business, pouring billions into new factories.

In 1993, the company was forced to make the first round of layoffs in the company’s history, cutting loose nearly 60,000 employees. By then, it was too late, and IBM was displaced by Intel and Microsoft. Rather than adapting to the times, IBM created a class of professional managers who emphasized quarterly profits over ideas. This crippled IBM’s ability to innovate.

4. Leave company culture underdetermined.

Companies are a lot like religions or cults: They need a set of values and beliefs that guide individual people toward the same goal. This allows people on the ground to autonomously make decisions in a way that’s consistent with how the larger company operates.

The problem is that even with more tools for communicating knowledge than ever before, knowledge is processed differently on a case-by-case basis. The economist Friedrich Hayek describes the problem as follows:

The peculiar character of the problem of a rational economic order is determined precisely by the fact that the knowledge of the circumstances of which we must make use never exists in concentrated or integrated form but solely as dispersed bits of incomplete and frequently contradictory knowledge which all separate individuals possess.

If you spend all of your time trying to determine exactly what your culture is, you won’t get anywhere, because culture is constantly changing. Empty platitudes like “our culture is about putting the customer first” treats culture statically, when in fact it changes constantly. As a company grows, these words lose their meaning.

If you try to set culture from the top, you’ll add process but stifle innovation. Twitter failed to build a software platform because it tried to overdetermine how third-party developers were interacting with the service, first by cannibalizing their products and ultimately by closing off API access to their product. If you overdetermine culture, you end up creating layers of bureaucracy that cripple your team’s ability to adapt and change.

When you’re building a platform for your team, your people are your platform. Rather than forcing a “right way of doing things,” give people building blocks. Cultural values should be memorable and underdetermined, meaning they’re fluid and adaptable. That allows your people to reinterpret culture in new and surprising ways to meet new circumstances.

Alibaba

Creating building blocks for culture means providing a stepping stone for your people and enabling individual behavior and human incentivizes to transform that stepping stone into something bigger. You can’t overdetermine culture. This is something that Alibaba has dome extremely well.

At a glance, Alibaba’s cultural values are unremarkable: customer first, teamwork, embrace change, integrity, passion, and commitment. What’s more important is how those compressed and invoked throughout the organization. At Alibaba, each of those six values is known internally as the “Six Vein Spirit Sword” — a reference to Jack Ma’s favorite series of kung-fu novels. Each vein in the metaphor maps to a value that guides how people behave.

The Six Vein Spirit Sword conveys the emotional, ineffable part of Alibaba’s culture, which has a higher bandwidth than the values alone. It empowers team members to believe in the company as something with greater purpose than any single individual, while also making those values closer and more achievable.

Cultural mysticism at Alibaba extends beyond the Six Vein Spirit Sword. From the start of the company, each team member took a name from the novelist Jin Yong’s book The Proud, Smiling Wanderer, a popular martial arts romance in China. To this day, each Alibaba employee is given a nickname that is used across the company, from emails to meetings and performance evaluations.

According to Alibaba VP Brian Wong:

Jin Yong’s characters are “like a brotherhood, like a band of brothers, it’s a group of people that are fighting for values of righteousness, loyalty.”

This elevates team members and gives them a starting point where they can actually take a value like “embrace change” and live it.

Alibaba’s cultural building blocks aren’t specific values or virtues possessed by fictional Chinese characters. They’re the sense of purpose created by these artifacts. While one of Alibaba’s six values can change, you can bet that throughout the history of Alibaba that the Six Vein Spirit Sword will remain. In doing so, Alibaba leaves its culture underdetermined — and able to change.

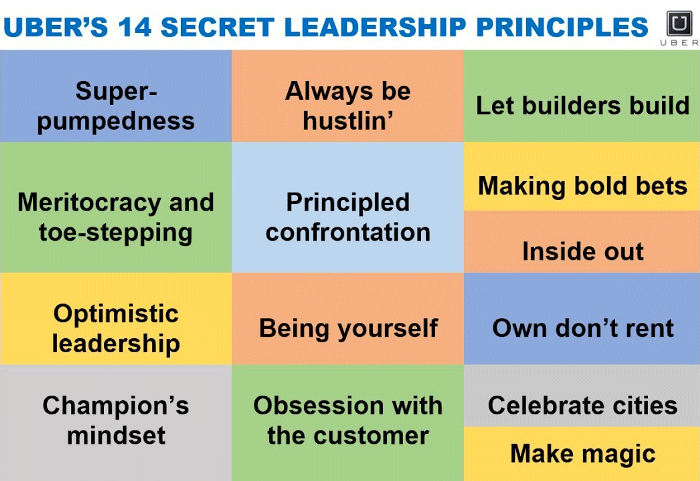

Uber

Once a culture is developed and embedded, it’s very difficult to change. Uber is perhaps the best-known example of this among startups today.

Under Travis Kalanick, the company’s culture of “toe-stepping” and “always be hustling” served the company as it rapidly grew from a black-car service in San Francisco to a global ride-hailing company operating in 600 cities around the world. While these values were helpful for getting the company to where it is today, it also explicitly determined the type of culture the company would have — making it extremely hard to shift gears today.

The company’s values included:

Uber’s business model depended on its ability to rapidly roll out technology developed in San Francisco and build network effects in new local markets. Uber’s culture promoted aggressive problem-solving and autonomous decision-making by team members. This allowed the company to adapt from the bottom up from city to city.

The downside was that these values determined not just results but how those results were achieved as well, promoting a cutthroat culture that prioritized growth above all else.

Last year, a series of scandals shook Uber to its core:

- Waymo alleged that former employee Anthony Levandowski stole trade secrets and took them to Uber to advance the company’s effort at building self-driving cars.

- Susan Fowler, a former engineer at Uber, published a 3,000-word blog post detailing her experience of sexism and harassment at the company.

- The New York Times revealed that Uber used a tool called Greyball to deny service to local authorities investigating the company.

- A video was posted to YouTube showing Travis Kalanick arguing with an Uber driver over prices. Kalanick is heard telling the driver, “Some people don’t like to take responsibility for their own shit.”

- Benchmark, one of Uber’s investors, launched a lawsuit accusing Kalanick of fraud and tried to unseat him from the board.

None of these events are isolated, nor can they be blamed solely on Kalanick. But as CEO, he set the tone and the precedent for acceptable behavior at the company. Even worse, this behavior determined Uber’s reputation and the way people perceived its brand.

When Lyft was founded, it flew in the face of regulations and let unvetted drivers pick up random people off the street. By this time, Uber was working with the government to establish guidelines for ridesharing.

As Brad Stone writes in his book The Upstarts, “It must have seemed unfair to Kalanick that Lyft had the better reputation, even though in some ways it was the more aggressive player.” The cost of overdetermining culture is that it’s extremely hard to change afterward, both internally and externally.

It’s a cost Uber will deal with for years to come. Cracks in your culture when you’re small will seem insignificant, but they compound over time like technical debt and will be much harder to fix down the line.

The Centenarian Organization

My uncle worked at Kodak for over 30 years, a duration that wasn’t unusual for his time. Companies used to hire and develop people over the course of a lifetime. Today, things are drastically different. At ten of the best-known Silicon Valley companies, the average employee stays a mere one to three years.

Startups today prioritize short-term gains over investing in their people. In part, that’s because companies are conditioned to think in two-year increments of time. You’re completely focused on the milestones you need to hit to raise your next round, with a distant end goal of eventually taking the company public. What people forget is that even after you raise more capital, you have to keep pushing forward and investing in your platform and your people.

The rare companies that have survived for 100 years or more have learned this lesson the hard way. Companies like Goldman Sachs and Coca-Cola don’t just plan for transitions between individual roles, but entire generations of employees. A company that’s built around a single benevolent dictator may see success in the short-term, but without a platform for its people, it can’t last.

If you want to build a company that can last 100 years, start by putting in place a set of core building blocks that enable new behavior and innovation. Design for upward mobility, nurturing leadership from the bottom-up. Create clean interfaces and autonomy between teams, so that as your teams scale they aren’t bottlenecked by dependencies between teams. Internalize external change, and retain the ability to burn the ships even as you grow larger as a company. Finally, leave culture undetermined so that your company can adapt and change over time.

Today, Silicon Valley has more talent and money than ever before. That makes it harder, not easier, to build a great company, because there’s a lot more competition between companies. The only way to gain leverage and break out is not just by investing in technology and product, but by turning your team into a high-performing and scalable platform.